Model-Free Control

While prediction is all about estimating the value function in an environment for which the underlying MDP is not known, Model-Free control deals with optimizing the value function. While many problems can be modelled as MDPs, in a lot of problems we don’t really have that liberty in some sense. The reasons why using an MDP to model the problem might not make sense are:

- MDP is unknown → In this case we have to sample experiences and somehow work with samples.

- MDP is known, but too complicated in terms of space and so, we again have to rely on experience

We can classify the policy learning process into two kinds based on the policy we learn and the policy we evaluate upon:

- On-Policy Learning → If we learn about policy \(\pi\) from the experiences sampled from \(\pi\) , then we are essentially learning on the job.

- Off-Policy Learning → If we use a policy \(\mu\) to sample the experiences, but our target is to learn about policy \(\pi\) , then we are essentially seeing someone else do something and learning how to do something else through that

Generalized Policy Iteration

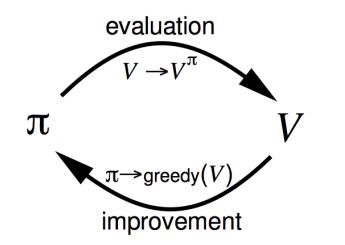

As explained before our process of learning can also be broken down into 2 stages:

- Policy Evaluation → Iteratively estimating \(v_\pi\) throught the samled experiences a.k.a iterative policy evaluation

- Policy Improvement → Generating a policy \(\pi' \geq \pi\)

The process of learning oscillates between these two states in sense → We evaluate a policy, then improve it, then evaluate it again and so on until we get the optimal policy $\pi^*$ and the corresponding optimal value \(v^*\). Thus, we could see this as state transitions, as shown below:

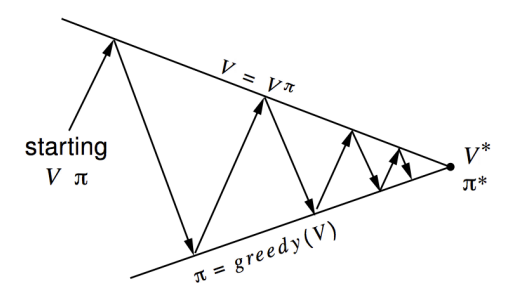

A really good way to look at convergence is shown below:

Each process drives the value function or policy toward one of the lines representing a solution to one of the two goals. The goals interact because the two lines are not orthogonal. Driving directly toward one goal causes some movement away from the other goal. Inevitably, however, the joint process is brought closer to the overall goal of optimality. The arrows in this diagram correspond to the behavior of policy iteration in that each takes the system all the way to achieving one of the two goals completely. In GPI one could also take smaller, incomplete steps toward each goal. In either case, the two processes together achieve the overall goal of optimality even though neither is attempting to achieve it directly. Thus, almost all the stuff in RL can be described as a GPI, since this oscillation forms the core of it, and as mentioned before the ideal solution is usually out of our reach due to computational limitations, and DP has its set of disadvantages.

On-Policy Monte-Carlo Control

Our iteration and evaluation steps are:

- We use Monte-Carlo to estimate the value

- We use greedy policy improvement to get a better policy

Ideally, we can easily use the value function \(v_\pi\) for evaluation and then improve upon it. However, if we look at the improvement step using \(v_\pi\) , w have the equation

\[\pi'(s) = \argmax_{a \in \mathcal{A}} R^a_s + P_{ss'}^a V(s')\]Here, to get the \(P_{ss'}^a\) we need to have a transition model, which goes against our target of staying model-free. The action-value \(q_\pi\), on the other hand, does not require this transition probability:

\[\pi'(s) = \argmax_{a \in A} Q(s,a)\]Thus, using \(q_\pi\) allows us to close the loop in a model-free way. Hence, we now have our 2-step process that needs to be repeated until convergence as:

- Iteratively Evaluate \(q_\pi\) using Monte-Carlo methods

- Improve to \(\pi' \geq \pi\) greedily

Maintaining Exploration and Stochastic Strategies

Greedy improvement is essentially asking us to select the policy that leads to the best value based on the immediate value that we see. This suffers from the problem of maintaining exploration since many relevant state-action pairs may never be visited → If \(\pi\) is a deterministic policy, then in following \(\pi\) one will observe returns only for one of the actions from each state. With no returns to average, the Monte Carlo estimates of the other actions will not improve with experience. Hence, we need to ensure continuous exploration. One way to do this is by specifying that the first step of each episode starts at a state-action pair and that every such pair has a nonzero probability of being selected as the start. This guarantees that all state-action pairs will be visited an infinite number of times within the limit of an infinite number of episodes. This is called the assumption of exploring starts. However, it cannot be relied upon in general, particularly when learning directly from real interactions with an environment. Thus, we need to look at policies that are stochastic in nature, with a nonzero probability of selecting all actions.

\(\epsilon\)-greedy Strategy

One way to make deterministic greedy policies stochastic is to follow an \(\epsilon\)-greedy strategy → We try all \(m\) actions with non-zero probability, and choose random actions with a probability \(\epsilon\), while maintaining a probability of \(1- \epsilon\) for choosing actions based on the greedy evaluation. Thus, by controlling \(\epsilon\) as a hyperparameter, we tune how much randomness our agent is willing to accept in its decision:

\[\pi(a|s) = \begin{cases} \frac{\epsilon}{m} + 1 - \epsilon \,\,\,\,\,\,\,\, if \,\,\, a^* = \argmax_{a \in A} Q(s,a) \\ \frac{\epsilon}{m} \,\,\,\,\,\,\,\, otherwise \end{cases}\]The good thing is that we can prove that the new policy that we get with the \(\epsilon\)-greedy strategy actually does lead to a better policy:

\[\begin{aligned} q_\pi(s, \pi'(s)) & = \sum_{a \in \mathcal{A}} \pi'(a|s) q_\pi(s,a) \\ & = \frac{\epsilon}{m} \sum_{a \in \mathcal{A}} \pi'(a|s) q_\pi(s,a) + ( 1- \epsilon) \max_{a \in \mathcal{A} } q_\pi(s,a) \\ & \geq \frac{\epsilon}{m} \sum_{a \in \mathcal{A}} \pi'(a|s) q_\pi(s,a) + ( 1- \epsilon) \sum_{a \in \mathcal{A}} \frac{\pi(a|s) - \frac{\epsilon}{m}}{1 - \epsilon} q_\pi(s,a) \\ & = v_\pi (s) \\ \therefore v_\pi(s') & \geq v_\pi (s) \end{aligned}\]GLIE

Greedy in the Limit with Infinite Exploration, as the name suggests, is a strategy in which we are essentially trying to explore infinitely, but reducing the magnitude of exploration over time so that in the limit the strategy remains greedy. Thus, a GLIE strategy has to satisfy 2 conditions:

-

If a state is visited infinitely often, then each action in that state is chosen infinitely often

\[\lim_{k \rightarrow \infty } N_k(s,a) = \infty\] -

In the limit, the learning policy is greedy with respect to the learned Q-function

\[\lim_{k \rightarrow \infty} \pi_k(a|s) = \bm{1} (a = \argmax_{a \in \mathcal{A}} Q_k(s, a'))\]

So, to convert our \(\epsilon\)-greedy strategy to a GLIE strategy, for example, we need to ensure that the magnitude of \(\epsilon\) decays overtime to 0. Two variants of exploration strategies that have been shown to be GLIE are:

- \(\epsilon\)-greedy with exploration with \(\epsilon_t = c/ N(t)\) where \(N(t)\) → number of visits to state \(s_t=s\)

-

Boltzmann Exploration with

\[\begin{aligned} & \beta_t(s) = \log (\frac{n_t(S)}{C_t(s)} ) \\ & C_t(s) \geq \max_{a,a'}|Q_t(s,a) - Q_t(s,a')| \\ & P(a_t = a | s_t = s ) = \frac{exp(\beta_t(s) Q_t(s,a))}{\sum_{b\in \mathcal{A}} exp(\beta_t(s) Q_t(s,a))} \end{aligned}\]

GLIE Monte-Carlo Control

We use Monte-Carlo estimation to get an estimate of the policy and then improve it in a GLIE manner as follows:

- Sample k\(^{th}\) episode using policy $\pi$ so that \(\{S_1, A_1, R_1, ....., S_T \} \sim \pi\)

-

For each state and action, update the Number of visitation

\[\begin{aligned} & N(S_t, A_t) \leftarrow N(S_t, A_t) + 1 \\ & Q(S_t, A_t) \leftarrow Q(S_t, A_t) + \frac{1}{N(S_t, A_t)} (G_t - Q(S_t, A_t) ) \end{aligned}\] -

Improve the policy based on action value as

\[\begin{aligned} & \epsilon \leftarrow \frac{\epsilon}{k} \\ & \pi \leftarrow \epsilon-greedy(Q) \end{aligned}\]

Thus, now we update the quality of each state-action pair by running an episode and update all the states that were encountered. Then we lip a coin with \(1- \epsilon\) probability of selecting the state-action pair with the highest \(Q(s,a)\) from all the possible choices and \(\epsilon\) probability of taking a random pair. Hence, we are able to ensure exploration happens with an $\epsilon$ probability, and this probability changes proportional to \(\frac{1}{k}\) which essentially allows us to get more greedy as \(k\) increases, with the hope that we converge to the optimal policy. In fact, it has

Off-Policy Monte-Carlo Control

To be able to use experiences sampled from a policy \(\pi'\) to estimate \(v_\pi\) or \(q_\pi\), we need to understand how the policies might relate to each other. To be even able to make a comparison, we first need to ensure that every action taken under \(\pi\) is also taken, at least occasionally, under \(\pi'\) → This allows us to guarantee representation of actions being common between the policies and thus, we need to ensure

\[\pi(s,a) > 0 \implies \pi'(s,a) > 0\]Now, let’s consider we have the $i^{th}$ visit to a state $s$ in the episodes generated from \(\pi'\) and the sequence of states and actions following this visit and let \(P_i(s), P_i'(s)\) denote the probabilities of that complete sequence happening given policies \(\pi, \pi'\) and let \(R_i(s)\) be the return of this state. Thus to estimate \(v_\pi(s)\) we only need to weigh the relative probabilities of \(s\) happening in both policies. Thus, the desired MC estimate after \(n_s\) returns from \(s\) is:

\[V(s) = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n_s} \frac{P_i(s)}{P_i(s')} R_i(s)}{\sum_{i=1}^{n_s} \frac{P_i(s)}{P_i(s')}}\]We know that the probabilities are proportiona to the transition probabilities in each policy and so

\[P_i(s_t) = \prod_{k=t}^{T_i(s) - 1} \pi(s_k, a_k) \mathcal{P}^{a_k}_{s_k s_{k+1}}\]Thus, when we take the ratio, we get

\[\frac{P_i(s)}{P_i'(s)} = \prod_{k=t}^{T_i(s) - 1} \frac{\pi(s_k, a_k)}{\pi'(s_k, a_k)}\]Thus, we see that the weights needed to estimate \(V(s)\) only depend on policies, and not on the dynamics of the environment. This is what allows off-policy learning to be possible. The advantage this gives us is that the policy used to generate behavior, called the behavior policy, may in fact be unrelated to the policy that is evaluated and improved, called the estimation policy. Thus, the estimation policy may be deterministic (e.g., greedy), while the behavior policy can continue to sample all possible actions!!

Importance Sampling

In MC off-policy control, we can use the returns generated from policy \(\mu\) to estimate policy \(\pi\) by weighing the target \(G_t\) based on the similarity between the policies. This is the essence of importance sampling, where we estimate the expectation of a different distribution based on a given distribution:

\[\begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}_{X \sim P}[f(X)] & = \sum P(X) f(X) \\ & = \sum Q(X) \frac{P(X)}{Q(X)}f(X) \\ & = \mathbb{E}_{X \sim Q} \bigg[ \frac{P(X)}{Q(X} f(X) \bigg] \end{aligned}\]Thus, we just multiple te importance sampling correlations along the episodes and get:

\[G^{\pi/\mu}_t = \frac{\pi(a_t|s_t)}{\mu(a_t|s_t)} \frac{\pi(a_{t+1}|s_{t+1})}{\mu(a_{t+1}|s_{t+1})} ... \frac{\pi(a_T|s_T)}{\mu(a_T|s_T)} G_t\]And now, we can use \(G^{\pi/\mu}_t\) to compute our value update for MC-control.

TD-Policy Control

The advantages of TD-Learning over MC methods are clear:

- Lower variance

- Online

- Incomplete sequences

We again follow the pattern of GPI strategy, but this time using the TD estimate of the target and then again encounter the same issue of maintaining exploration, which leads us to on-policy ad off-policy control. As was the case with MC control, we need to remain model-free and so we shift the TD from estimating state-values to action-values. We know that formally, they both are equivalent and essentially Markov chains.

On-Policy Control : SARSA

We can use the same TD-target as state values to get the update for state-action pairs:

\[Q(s_t, a_t) \leftarrow Q(s_t, a_t) + \alpha \big[ R_{t+1} + \gamma Q(s_{t+1}, a_{t+1}) - Q(s_t, a_t) \big]\]This is essentially operating over the set of current states and action, one step look-ahead of the same values and the reward of the next pair → \((s_t, a_t, r_{t+1}, s_{t+1}, a_{t+1})\) - and the order in which this is written is State → Action → Rewards → State → Action. Thus, this algorithm is called SARSA. We can use SARSA for evaluating our policies and then improve the policies, again, in an $\epsilon$-greedy manner. SARSA converges to \(q^*(s,a)\) under the following conditions:

-

GLIE sequences of policies $$\pi_t(a s)$$ -

Robbins-Monro sequence of step-sizes \(\alpha_t\)

\[\begin{aligned} & \sum_{t=1}^\infty \alpha_t = 0 \\ & \sum_{t=1}^\infty \alpha^2_t < \infty \end{aligned}\]

We can perform a similar modification on SARSA to to extend it to n-steps by defining a target based on n-step returns:

\[\begin{aligned} & q_t^{(n)} = r_{t+1} + \gamma r_{t+2} + \gamma^2 r_{t+3} + ... + \gamma^{n-1} r_{t+n} + \gamma^n Q(s_{t+n}) \\ \therefore \,\,\,& Q(s_t, a_t) \leftarrow Q(s_t, a_t) + \alpha \big[ q_t^{(n)} - Q(s_t, a_t) \big] \end{aligned}\]Additionally, we can also formulate a forward-view SARSA(\(\lambda\)) by combining n-step returns:

\[q_t^\lambda = (1 - \lambda) \sum _{n=1}^\infty \lambda ^{n-1} q_t^{(n)}\]and just like TD(\(\lambda\)), we can implement Eligibility traces in online algorithms, in which case there will be one eligibility trace for each state-action pair:

\[\begin{aligned} & E_0(s,a) = 0 \\ & E_t(s,a) = \gamma \lambda E_{t-1}(s,a) + \bm{1}(s,a) \\ \therefore \,\,\, & Q(s_t, a_t) \leftarrow Q(s_t, a_t) + \alpha \, E_t(s,a) \big[ q_t^{(n)} - Q(s_t, a_t) \big] \end{aligned}\]TD Off-Policy Learning : Q-Learning

For off-policy learning in TD, we can again look at the relative weights and use importance sampling. However, since the lookahead is only one-step and not n-step sequence sampling, we only need a single importance sampling correction to get

\[V(s_t) \leftarrow V(s_t) + \alpha \, \bigg( \frac{\pi(a_t|s_t)}{\mu(a_t|s_t)} (R_{t+1} + \gamma \, V(s_{t+1})) - V(s_t) \bigg)\]The obvious advantage is the requirement of only a one-step correlation, which leads to much lower variance. One of the most important breakthroughs in reinforcement learning was the development of Q-learning, which does not require importance sampling. The simple idea that makes the difference is:

- we choose our next action from the behavior policy i.e \(a_{t+1} \sim \mu\) BUT we use the alternative action sampled from the target policy \(a' \sim \pi\) to update towards. Thus, our equation becomes:

-

\[Q(s, a) \leftarrow Q(s, a) + \alpha \big[ R + \gamma \max_{a'} Q(s', a') - Q(s, a) \big]\]Then, we allow both behavior and target policies to improve → This means that $$\pi(s_{t+1} a_{t+1} ) = \argmax_{a’} Q(s_{t+1}, a’)\(while\)\mu(s_{t+1} a_{t+1} ) = \argmax_{a} Q(s_{t+1}, a)$$ . Thus, our final equation simplifies to:

This dramatically simplifies the analysis of the algorithm. We can see that all that is required for correct convergence is that all pairs continue to be updated.