Bayesian Optimization

The general optimization problem can be stated as the task of finding the minimal point of some objective function by adhering to certain constraints. More formally, we can write it as

\[\min_x f(x) \,\,\,\, s.t \,\,\,\, g(x) \leq 0 \,\,\,, \,\,\, h(x) = 0\]We usually assume that our functions \(f, g, h\) are differentiable, and depending on how we calculate the first and second-order gradients (The Jacobians and Hessians) of our function, we designate the different kinds of methods used to solve this problem. Thus, in a first-order optimization problem, we can evaluate our objective function as well as the Jacobian, while in a second-order problem we can even evaluate the Hessian. In other cases, we impose some other constraints on either the form of our objective function or do some tricks to approximate the gradients, like approximating the Hessians in Quasi-Newton optimization. However, these do not cover cases where \(f(x)\) is a black box. Since we cannot assume that we fully know this function our task can be re-formulated as finding this optimal point \(x\) while discovering this function \(f\). This can be written in the same form, just without the constraints

\[\min _x f(x)\]KWIK

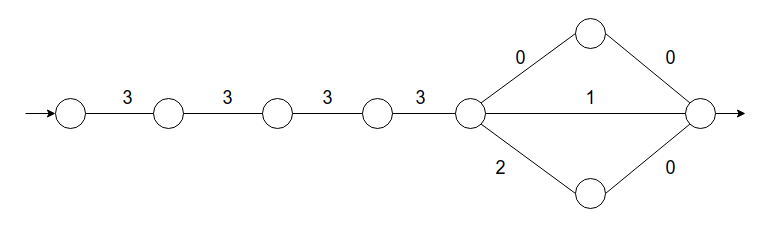

To find the optimal \(x\) for an unknown \(f\) we need to explicitly reason about what we know about \(f\). This is the Knows What It Knows framework. I will present an example from the paper that helps understand the need for this explicit reasoning about our function. Consider the task of navigating the following graph:

Each edge in the graph is associated with a binary cost and let’s assume that the agent does not know about these costs beforehand, but knows about the topology of the graph. Each time an agent moves from one node to another, it observes and accumulates the cost. An episode is going from the source on the left to the sink on the right. Hence, the learning task is to figure out the optimal path in a few episodes. The simplest solution for the agent is to assume that the costs of edges are uniform and thus, take the shortest path through the middle, which gives it a total cost of 13. We could then use a standard regression algorithm to fit a weight vector to this dataset and estimate the cost of the other paths, simply based on the nodes observed so far, which gives us 14 for the top, 13 for the middle, and 14 for the bottom paths. Hence, the agent would choose to take the middle path, even though it is suboptimal as compared to the top one.

Now, let’s consider an agent that does not just fit a weight vector but reasons about whether it can obtain the cost of edges with the available data. Assuming the agent completed the first episode through the middle path and accumulated a reward of 13, the question it needs to answer is which path to go for next. In the bottom path cost of the penultimate node is 2, which can be figured out from the costs of nodes already visited

\[3 - 1 = 2\]This gives us more certainty than the uniform assumption that we started with. However, this kind of dependence does not really exist for the upper node since the linear combination does not work on the nodes already visited. If we incorporate a way for our agent to say that it is not sure about the answer to the cost of the upper nodes, we can essentially incentivize it to explore the upper node in the next round, allowing our agent to visit this node and discover the optimal solution. This is similar to how we discuss the exploration-exploitation dilemma in Reinforcement Learning.

MDP framework

Motivated from the previous section and based on the treatment done here, we can model our solver as an agent and the function as the environment. Our agent can sample the value of the function in a range of possible values and in a limited budget of samples, it needs to find the optimal \(x\). The observation that comes after sampling from the environment is the noisy estimate of \(f\), which can call \(y\). Thus, we can write our function as the expectation over these outputs

\[f( x) = \mathbb{E}\big [ y |f(x) \big ]\]We can cast this as a Markov Decision Process where the state is defined by the data the agent has collected so far. Let’s call this data \(S\). Thus, at each iteration \(t\), our agent exists in a state \(S_t\) and needs to make a decision on where to sample the next \(x_t\). Once it collects this sample, it adds this to its existing knowledge

\[S_{t+1} = S_t \cup \{x_t, f_t \}\]We can create a policy \(\pi\) that our agent follows to take an action from a particular state

\[\pi : S_t \rightarrow x_t\]| Hence, the agent operates with a prior over our function \(P(f)\) , and based on this prior it calculates a deterministic posterior $$P_\pi (S | x_t, f)$$ by multiplying it with the expectation over the outputs. |

Since the agent does not know \(f\) apriori, it needs to calculate a posterior belief over this function based on the accumulated data

\[P(f|S) = \frac{P(S|f) P(f)}{P(S)}\]| With the incorporation of this belief, we can define an MDP over the beliefs with stochastic transitions. The states in this MDP are the posterior belief $$P(f | S)$$ . Thus, the agent needs to simulate the transitions in this MDP and it can theoretically solve the optimal problem through something like Dynamic programming. However, this is difficult to compute. |

Bayesian Methods

| This is where Bayesian methods come into the picture. They formulate this belief $$P(f | S)$$ as a Bayesian representation and compute this using a gaussian process at every step. After this, they use a heuristic to choose the next decision. The Gaussian process used to compute this belief is called surrogate function and the heuristic used is called an Acquisition Function. We can write the process as follows: |

- Compute the posterior belief using a surrogate Gaussian process to form an estimate of the mean \(\mu(x)\) and variance around this estimate \(\sigma^2(x)\) to describe the uncertainty

- Compute an acquisition function \(\alpha_t(x)\) that is proportional to how beneficial it is to sample the next point from the range of values

-

Find the maximal point of this acquisition function and sample at that next location

\[x_t = \argmax_x \alpha_t(x)\]

This process is repeated a fixed number of iterations called the optimization budget to converge to a decently good point. Three poplar acquisition functions are

-

Probability of Improvement (MPI) → The value of the acquisition function is proportional to the probability of improvement at each point. We can characterize this as the upper-tail CDF of the surrogate posterior

\[\alpha_t( x) = \int_{-\infty}^{y_{opt}}\mathcal{N} \big (y|\mu(x), \sigma (x) \big ) dy\] -

Expected Improvement (EI) → The value is not just proportional to the probability, but also to the magnitude of possible improvement from the point.

\[\alpha_t(x) = \int_{-\infty}^{y_{opt}}\mathcal{N} \big (y|\mu(x), \sigma (x) \big ) \big [ y_{opt} - y\big ] dy\] -

Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) → We control the exploration through the variance and control parameter and exploit the maximum values

\[\alpha_t(x) = -\mu(x) + \beta\sigma(x)\]

The evaluation of this maximization of the acquisition function is another non-linear optimization problem. However, the advantage is that these functions are analytic and so, we can solve for jacobians and Hessians of these, ensuring convergence at least on a local level. To make this process converge globally, we need to optimize from multiple start points from the domain and hope that after all these random starts the maximum found by the algorithm is indeed the global one.

Hyperparameter Tuning

One of the places where Global Bayesian Optimization can show good results is the optimization of hyperparameters for Neural Networks. So, let’s implement this approach to tune the learning rate of an Image Classifier! I will use the KMNIST dataset and a small ResNet-9 Model with a Stochastic Gradient Descent optimizer. Our plan of attack is as follows:

- Create a training pipeline for our Neural Network with the Dataset and customizable learning rate

- Cast the training and inference into a an objective function, which can serve as ou blackbox

- Map the inference to an evaluation metric that can be used in the optimization procedure

- Use this function in a global bayesian optimization procedure.

Creating the training pipeline and Objective Function

I have used PyTorch and the lightning module to create a boilerplate that can be used to train our network. Since KMNIST and ResNet architectures are already available in PyTorch, all we need to do is customize the ResNet architecture for MNIST, which I have done as follows

def create_resnet9_model() -> nn.Module:

'''

Function to customize the RESNET to 9 layers and 10 classes

Returns

--------

torch.module

Pytorch Module of the Model

'''

model = ResNet(BasicBlock, [1, 1, 1, 1], num_classes=10)

model.conv1 = torch.nn.Conv2d(1, 64, kernel_size=(7, 7), stride=(2, 2), padding=(3, 3), bias=False)

return model

#

class ResNet9(pl.LightningModule):

def __init__(self, learning_rate=0.005):

'''

Pytorch Lightning Module for training the RESNET with SGD optimizer

Parameters

-----------

learning_rate: float

Learning rate to be used for training every time since it is an

optimization parameter

'''

super().__init__()

self.model = create_resnet9_model()

self.loss = nn.CrossEntropyLoss()

self.learning_rate = learning_rate

@auto_move_data

def forward(self, x):

return self.model(x)

def training_step(self, batch, batch_no):

x, y = batch

loss = self.loss(self(x), y)

return loss

def configure_optimizers(self):

return torch.optim.SGD(self.parameters(), lr=self.learning_rate)

Once this is done, our next step is to use the training pipeline and cast it into an objective function. For this, we need to evaluate our model somehow. I have used the balanced accuracy as an evaluation metric, but any other metric can also be used (like the AUC-ROC score)

def objective( lr=0.1,

epochs=1,

gpu_count=1,

iteration=None,

model_dir='./outputs/models/',

train_dl=None,

test_dl = None

):

'''

The objective function for the optimization procedure

Parameters

-----------

lr: float

learning Rate

epochs: int

Epochs for training

gpu_count: int

Number of GPUs to be used (0 for only CPUs)

iteration: int

Current iteration

model_dir: str

directory to save model checkpoints

train_dl: Torch Dataloader

Dataloader for training

test_dl: Torch Dataloader

Dataloader for inference

Returns

---------

float

balanced Accuracy of the model after inference

'''

save = False

checkpoint = "current_model.pt"

model = ResNet9(learning_rate=lr)

trainer = pl.Trainer(

gpus=gpu_count,

max_epochs=epochs,

progress_bar_refresh_rate=20

)

trainer.fit(model, train_dl)

trainer.save_checkpoint(checkpoint)

inference_model = ResNet9.load_from_checkpoint(

checkpoint, map_location="cuda")

true_y, pred_y, prob_y = [], [], []

for batch in tqdm(iter(test_dl), total=len(test_dl)):

x, y = batch

true_y.extend(y)

model.freeze()

probabilities = torch.softmax(inference_model(x), dim=1)

predicted_class = torch.argmax(probabilities, dim=1)

pred_y.extend(predicted_class.cpu())

prob_y.extend(probabilities.cpu().numpy())

if save is False:

os.remove(checkpoint)

return np.mean(balanced_accuracy_score(true_y, pred_y))

Implementing Bayesian Optimization

As mentioned in the previous sections, we first need a Gaussian Process as a surrogate model. We can either write it from scratch or just use some open-sourced library to do this. Here, I have used sci-kit learn to create a regressor

# Create the Model

m52 = sklearn.gaussian_process.kernelsConstantKernel(1.0) * Matern( length_scale=2.0,

nu=1.5

)

model = sklearn.gaussian_process.GaussianProcessRegressor(

kernel=m52,

alpha=1e-10,

n_restarts_optimizer=100

)

Once th Gaussian process is established, we now need to write the acquisition function. I have used the Expected Improvements acquisition function. The core idea can be re-written as proposed by Mockus

\[EI(x) = \begin{cases} \big( \mu_t(x) - y_{max} - \epsilon \big ) \Phi(Z) + \sigma_t (x) \phi(Z) &\sigma_t(x) > 0 \\ 0 & \sigma_t(x) > 0 \end{cases}\]Where

\[Z = \frac{\mu_t(x) - y_{max} - \epsilon}{\sigma_t(x) }\]and \(\Phi\) and \(\phi\) are the PDF and CDF functions. This formulation is an analytical expression that achieves the same result as our earlier formulation and we have added \(\epsilon\) as an exploration parameter. This can be implemented as follows

def _acquisition(self, X, samples):

'''

Acquisition function using hte Expected Improvement method

Parameters

-----------

X : N x 1

Array of parameter points observed so far

X_samples : N x 1

Array of Sampled points between the bounds

Returns

--------

float

Expected improvement

'''

# calculate the max of surrogate values from history

mu_x_, _ = self.surrogate(X)

max_x_ = max(mu_x_)

# Get the mean and deviation of the samples

mu_sample_, std_sample_ = self.surrogate(samples)

mu_sample_ = mu_sample_[:, 0]

# Get the improvement

with np.errstate(divide='warn'):

z = (mu_sample_ - max_x_ - self.eps) / std_sample_

EI_ = (mu_sample_ - max_x_ - self.eps) * \

scipy.stats.norm.cdf(z) + std_sample_ * scipy.stats.norm.pdf(z)

EI_[std_sample_ == 0.0] = 0

return EI_

the self.surrogate() function is just predicting using the Gaussian process earlier written. Once we have our expected improvements, we need to optimize our acquisition by maximizing over these expected improvements

def optimize_acq(self, X):

'''

Optimization of the Acquisition function using a maximization check of the outputs

Parameters

-----------

X : N x 1

Array of parameter points

Returns

--------

float

Next location of the sampling point based on the Maximization

'''

# Calculate Acquisition value for each sample

EI_ = self._acquisition(X, self.X_samples_)

# Get the index of the largest Score

max_index_ = np.argmax(EI_)

return self.X_samples_[max_index_, 0]

Putting it all together

Now that we have our optimization routines, we just need to combine them with our objective function into a loop and we are done. In my code, I have implemented the optimization as a class and I pass the paramters to this class. So, the main loop looks as follows:

budget = 10

train_data = KMNIST("kmnist", train=True, download=True, transform=ToTensor())

test_data = KMNIST("kmnist", train=False, download=True, transform=ToTensor())

train_dl = DataLoader(train_data, batch_size=batch_size, shuffle=True, num_workers=8 )

test_dl = DataLoader(test_data, batch_size=batch_size, num_workers=8)

# sample the domain

X = np.array([np.random.uniform(0, 1) for _ in range(init_samples)])

y = np.array([objective(lr =x,

epochs=init_epochs,

gpu_count=gpu_count,

train_dl=train_dl,

test_dl=test_dl

) for x in X])

X = X.reshape(len(X), 1)

y = y.reshape(len(y), 1)

for i in range(budget):

# fit the model

B.model.fit(X, y)

# Select the next point to sample

X_next = B.optimize_acq(X, y)

# Sample the point from Objective

Y_next = objective( lr=X_next,

epochs=epochs,

gpu_count=gpu_count,

model_dir= output_dir+"/models/",

iteration=i+1,

train_dl= train_dl,

test_dl = test_dl

)

print(f"LR = {X_next} \t Balanced Accuracy = {Y_next*100} %")

# Plots for second iteration onwards

B.plot(X, y, X_next, i+1)

# add the data to History

X = np.vstack((X, [[X_next]]))

y = np.vstack((y, [[Y_next]]))

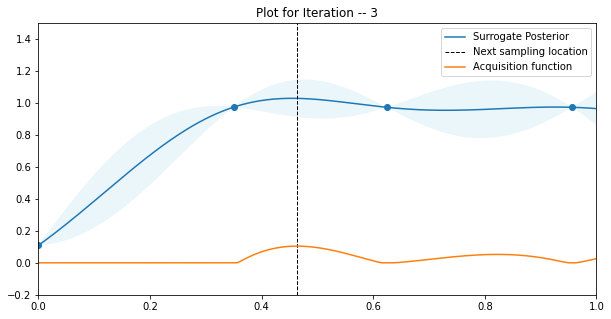

Here, I have used a budged to 10 function evaluations in the main loop and 2 function evaluations before the first posterior estimate. An exemplary plot of what comes out at the end is shown below

The vertical axis is the Balanced Accuracy and the horizontal axis is the learning rate. As can be seen, this is the third iteration of the main loop, with 2 points sampled as an initial estimate, and the acquisition function is the highest at the region with the balance of uncertainty and value of the mean.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: